In 2017, I worked with the late Paul Sartin to relaunch the Whitchurch Folk Club here in Hampshire. I say “relaunch” even though there never has been (to my knowledge) a club of that name. The local folk club that ran regularly between the 1970s and the early 90s was named after a now-defunct local pub, The Red House, which we used for sessions until its closure a year or so before lockdown. What with Paul’s passing, it seems as though we’ll have to gather our wits about us and re-relaunch the club again when the time is right.

But that’s only the half of it.

Shortly before his funeral, Paul’s sons announced that, rather than flowers, they would like money to go toward an even bigger relaunch: that of the Whitchurch Folk Festival, which also ran until the late 80s and early 90s. Paul and I often discussed ways in which we could make this happen, and, with the help of a very kind local with plenty of funding experience, even applied for grants earlier this year to try and get something off the ground. Money aside, the real issue was that neither of us had the experience required. Relaunch a folk club? Sure, we could do that. Conjure a whole folk festival into existence out of thin air? Not quite so easy.

We had the passion, though, not to mention a fundamental reason for doing it. You see, Whitchurch is the location of a successful visit by an Edwardian folk song collector. The 10 songs that George Gardiner collected at No.2 Weir Cottages were a source of continued fascination to Paul – he recorded several of them over the course of his career and sang two of them so often that they were as synonymous with him as they are with the town itself (probably more so if you don’t happen to live in Hampshire). We talked often about recording an album of the songs together (10 seemed like an absolute gift as far as album tracklistings were concerned), but never got much further than arranging three of them and recording one of them for a TV crew in the weaving shed at Whitchurch Silk Mill (see the video below).

It always made sense that Whitchurch Folk Festival should ride again, and the case for a relaunch seems even stronger given the love that Paul had for the songs and the town itself. They’re indelibly linked now, and since he wanted so dearly to make it happen, I will do what I can to help his boys make it so. A number of people with a great amount of combined experience have already been in touch to offer their assistance – my huge thanks for offering an initial glimmer of hope.

A number of years ago, I researched and wrote an article about the songs, the source singers and the collector that combined to leave us this wonderful musical legacy. I republish it here for those visitors coming to Whitchurch on October 22nd to celebrate Paul’s work with our folk club. While the evening concert has now sold out, the church and its grounds will be open during the day, hosting a book of condolences, Morris dancing, a singing workshop on the local songs, and performances by local musicians who knew and played with Paul, as well as his beloved choir. If you would like to join us, you are more than welcome. Make sure you take a little time to wander up to the Weir and contemplate where the local fascination with these songs – nurtured by Paul himself – all began.

In this article, you’ll find…

- Notes on folk song collecting

- Who was George Gardiner

- Henry Lee and Whitchurch

- The Whitchurch Songs

- Paul Sartin’s recordings of the Whitchurch Songs

Notes on folk song collecting

Newcomers to folk music are often surprised to find that ‘collecting’ was once, and to a certain extent still is, a large part of the tradition. While the idea of approaching someone in a pub in England and asking them to sing old local songs might seem peculiar to anyone who frequents the modern British boozer, it’s apparently still acceptable in other places. Indeed, when I interviewed Ian Lynch (Lankum) on this blog, he told me he often records old-timers singing in Irish pubs on his phone, and will regularly head off the beaten track to find places with that purpose in mind.

Back in late Victorian/early Edwardian times, there was something of a fevered passion among the middle classes for the collecting of rural, traditional songs. Notable collectors include Cecil Sharp (after whom Cecil Sharp House, the headquarters of the English Folk Dance and Song Society, is named) and the classical composer, Vaughan Williams. Along with a growing cadre of similarly-minded people, they would wander out into the sticks and approach the local folk in the hope of noting down regional songs. While it certainly conjures up images of confused exchanges between smartly-dressed toffs and somewhat bemused farmhands, many believe that it saved a dying tradition. It was believed that the songs of the people, so to speak, were not being recorded in any way, so documentation of this nature helped to keep what we now recognise as ‘traditional folk songs’ alive.

George Gardiner and Whitchurch

George Gardiner, a Scottish classical scholar, began indulging his interest in folk song collecting in Bath in 1903. He called his work a “systematic study of the folk songs of Europe”, although – certainly as far as I’m aware – his legacy can be seen most vividly in the collections he made in and around Hampshire. The Full English website (which digitally archives traditional English folk songs based at Cecil Sharp House) suggests that he collected approximately 1,100 songs by 1907, and in a letter that he wrote to the Hampshire Field Club and Archeological Society in 1906, he reported that at least 350 of these had been collected in this county.

George Gardiner, a Scottish classical scholar, began indulging his interest in folk song collecting in Bath in 1903. He called his work a “systematic study of the folk songs of Europe”, although – certainly as far as I’m aware – his legacy can be seen most vividly in the collections he made in and around Hampshire. The Full English website (which digitally archives traditional English folk songs based at Cecil Sharp House) suggests that he collected approximately 1,100 songs by 1907, and in a letter that he wrote to the Hampshire Field Club and Archeological Society in 1906, he reported that at least 350 of these had been collected in this county.

Gardiner visited Whitchurch, Hampshire, in May 1906, summoned by a member of the Lee family from whom he would eventually collect. In the sleevenotes to their 2010 album, Through Lonesome Woods, Hampshire duo The Askew Sisters write: “This lovely waltzy version was collected by George Gardiner from Mrs Etheridge in Southampton in June 1906. However, the text was incomplete, so Gardiner placed an ad in the Hampshire Chronicle appealing for other verses. He received a reply from Mrs Lee of Whitchurch containing a full set of verses (which we sing here) and her letter can still be found in the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library at Cecil Sharp House.”

His visit to the town was nothing out of the ordinary – his letter describes the visit as part of a trek through, “Old Alresford, Bishops’s Sutton, Micheldever, Whitchurch [and] Lyndhurst”. Most interestingly, it also reveals his working methods…

People sometimes ask me how I discover my singers. Well I simply ask anybody. If I am driving to Micheldever or Lyndhurst, I tell the driver what I am doing, and ask him to name anyone who can sing an old-world song. If he cannot tell, I go to the blacksmith or the innkeeper, who know the neighbourhood as well as most men, and I am invariably received with the utmost civility. When I make my first visit I explain what I am doing and the kind of song I want, and when people really understand my object I find them not only willing but eager to help me. Besides, a singer is always a jolly good fellow.

…and some of the frustrations that went with his occupation:

One day I walked for miles near Lyndhurst and Minstead without making any headway. Everyone was working till sunset, and came home rather in a sleeping than a singing mood. I politely said to some of the people, ‘This is really too bad. My song-harvest is at a standstill. To oblige me, could you not put off that haymaking for a year?’ They would not consent.

On other occasions he seems to have been entirely misunderstood:

Once I called on an old lady who was prepared for my visit. Unfortunately, someone else answered the door, and when I spoke of old songs the answer was, “We don’t want old songs. We have no money to give for old songs. We really don’t require any today.”

We know, also, that he usually worked alone to locate performers and note down the lyrics of their songs, before sending learned colleagues in to take down the tunes. Often, these colleagues were unable to locate the performers, so Gardiner’s collected songs are occasionally without melodies. However, it seems that they were relatively lucky on this occasion, quite possibly because they had an address for the performer.

Henry Lee and Whitchurch

In 1906, when Gardiner visited, Henry Lee lived at number 2 Weir Cottages, just off the Winchester Road as you enter Whitchurch from the South. A gardener and labourer, he was located on the quaint country lane with his daughters, and the collector managed to note down 10 songs (plus one repetition). Some of these are well-known in the canon, although it seems to be the case that even the better-known songs have quirks that are unique to Whitchurch.

So, what do we know about Henry Lee? More than you might imagine, as it happens. Consulting local historian, Martin Smith, we found that Lee was born in Barehill Street (now Newbury St), Whitchurch on 3rd September, 1837, to Charles and Harriet Lee. While the family seems to have disappeared for a spell when Henry was about 13 or 14, he turns up again in the 1861 census, 25 years old and employed as a farm labourer.

Whichurch inhabitants should look away now, as what follows is a little difficult to stomach. At some point following the 1861 census, it would seem that he relocated up the road to Overton (I know, I know… I warned you), where he married Ann, an Overton girl. However, by the time of the 1881 census he was back, now living at ‘Fishing Cottage’, which would have been located on modern-day Test Road.

10 years pass again before he makes another appearance, this time married to a woman called Maria, having fathered three children, Henrietta, Harriet and Marian (we can only assume that Ann passed away, childless). By this point he had relocated to The Weir, where he was employed as a miller’s labourer.

The Whitchurch songs

By the time George Gardiner arrived in North Hampshire, Henry Lee would have been 67 years old, still living at The Weir (although Martin Smith thinks he may have been living further up the lane in a cottage near Fulling Mill). It seems that he’d also fathered his youngest daughter, 17 years old at this point, who didn’t make it into any of the earlier records. He’d changed his occupation once again, too, possibly due to his advancing years. He was now a gardener.

Gardiner collected a surprisingly large clutch of songs given the relatively small size of the town, and I can’t help wonder whether he might have collected more than have been accounted for. In the letter quoted above he actually makes mention of collecting at the local workhouse (now The Gables), explaining again that the rural workers were far too busy to help him out at that time of the year, and that he’d collected 50 songs at Basingstoke workhouse, 45 at Southampton, 25 at Fareham and 20 at Winchester – clearly they made for unquestionably fertile ground.

It’s hard to say whether he actually had any success at Whitchurch workhouse; the records show that he got all he came for from Henry Lee and his daughter, “Miss Lee” (who we can only suppose was the aforementioned Rosa).

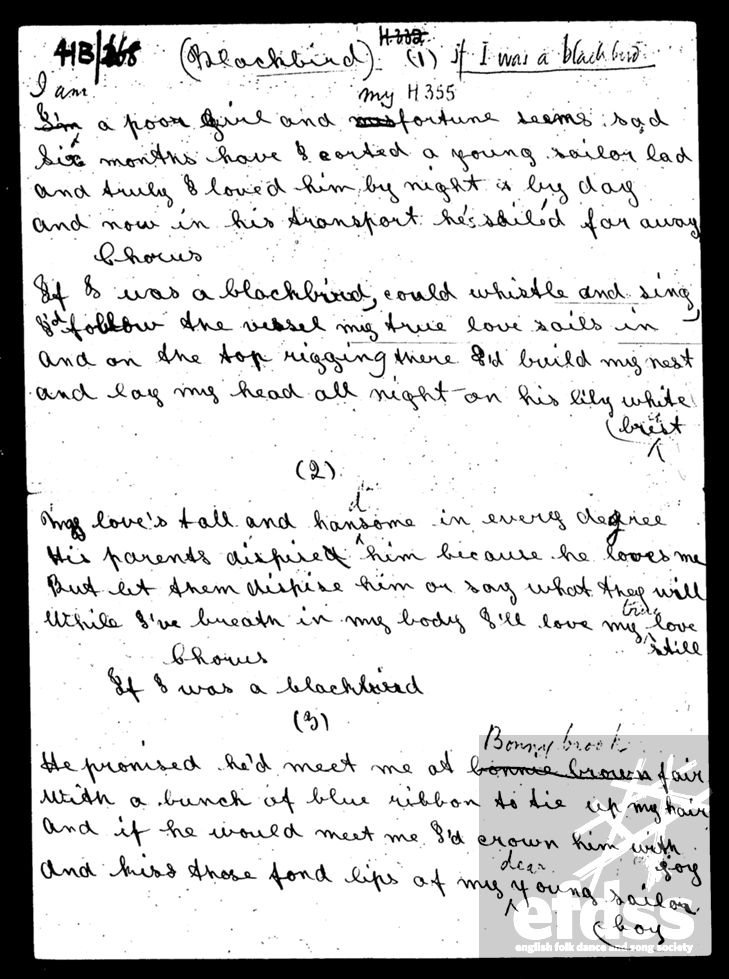

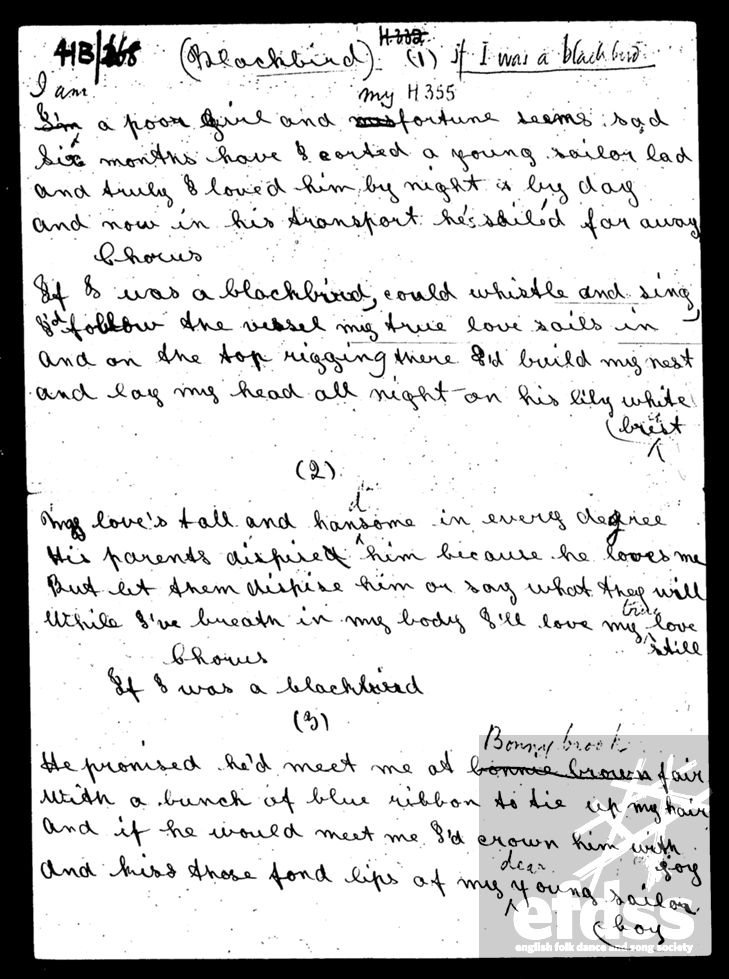

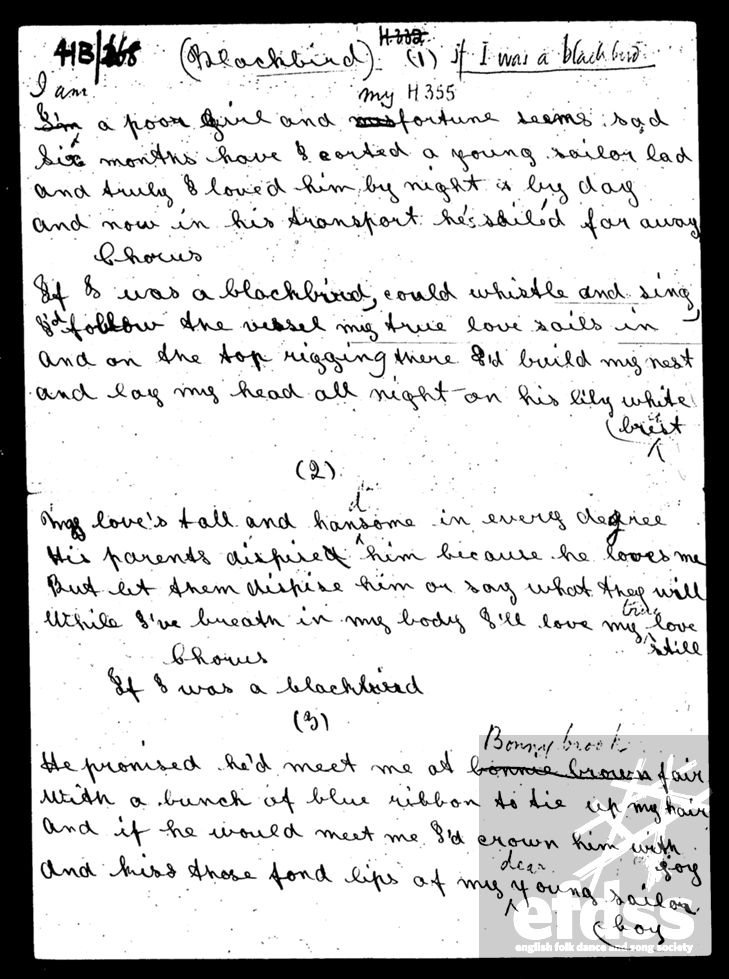

Of the 11 pieces that reside in the archive at Cecil Sharp House, 10 are attributed to Henry and one to Miss Lee. It’s slightly peculiar that Miss Lee’s song is a replica of one of Henry’s, and given that they appear to be identical, it’s possible that one of these was re-recorded for safekeeping. It’s certainly one of the strongest songs in the Lee family’s crop. The handwritten version of ‘If I Was a Blackbird’ [Roud 387], pictured above, is attributed to Henry, while the typed record is attributed to his daughter.

The full collection consists of the following songs (the links will take you to the relevant entry in the digital archive at The Full English):

- Blackbird (attributed to Henry Lee) [Roud 387]

- Haymaking Song [Roud 153]

- The Crocodile [Roud 886]

- The Collier’s Son [Roud 1129]

- The Gallant Poachers [Roud 793]

- The Wild Rover [Roud 1173]

- In Reading Town [Roud 218]

- If I Was a Blackbird (attributed to Miss Lee) [Roud 387]

- Just as the Tide was Flowing [Roud 1105]

- Pretty Susan the Pride of Kildare [Roud 962]

- The Unfortunate Lad/Lass [Roud 2]

Fans of traditional folk music will, of course, recognise a good number of those titles and promptly question the claim that they belong to Whitchurch in any way. And it’s true that a song about the ‘Pretty Susan the Pride of Kildare’ is unlikely to have originated just up the A34 from Winchester. However, that’s one of the wonderful things about folk music – these songs travelled and took on a life of their own. While it might be hard to place their exact origin, the quirks, whether lyrical or melodic, that Henry Lee and his daughter offered up to George Gardiner appear to have found their way into the piece via a life led largely in this part of Hampshire. More to the point, had these versions not been taken down in Whitchurch at that moment in time – on The Weir in May, 1906 – it’s unlikely we’d have any record of their existence at all.

Personally, I find all of this incredibly inspiring. I love the fact that we’re able to trace a handful of songs back to a very specific time, if not within living memory then certainly to a point at which some form of written snapshot still exists. And it’s wonderful, too, that we know exactly where these songs were being sung, not to mention a little about the singers and something of the collector, too. These are songs with a postcode, and in this case the postcode is RG28 7JA.

I regularly walk past The Weir cottages and up to Fulling Mill when walking our dog, and I always imagine Henry Lee and his daughter, possibly sat on the fence that edges the neighbouring field, singing their songs to a gentleman of some standing, possibly wondering what his interest in them might be, not imagining for a second that we’d be writing about them and singing their songs over a century later. These bridges through time are, to me, what makes traditional folk music such an endlessly fulfilling genre.

Paul Sartin’s recordings of the Whitchurch songs

If I Was a Blackbird [Roud 387]

As I’ve written before, Paul Sartin would sing ‘If I Was a Blackbird’ [Roud 387] at the drop of a hat. I can’t count the number of times I heard him sing it, accompanied him singing it, or sometimes even implored him to sing something else. He recorded it with Belshazzar’s Feast on their 2014 live album, The Whiting’s On the Wall, he arranged it for his book, Community Choir Collection (2016), and he produced it on the Hen Party album, Nobody Here but Us (1998). The last time I heard him sing it was at FolkEast in 2022, only a matter of weeks before his death. Fortunately, we caught a clip of his unaccompanied performance on camera, seen above.

The Wild Rover [Roud 1173]

One of the best-known traditional folk songs in its “no, nay, never” form, the Whitchurch version is perhaps a little more subtle. I have very fond memories of singing it in the Red House pub here in Whitchurch, often with a cheeky wink or nod to whoever was serving behind the bar. He recorded it with Belshazzar’s Feast on their Find the Lady album (2010), produced by Jim Moray. He also arranged it for his book, Community Choir Collection (2016).

My thanks go to Reinhard Zierke for his help in researching this piece. To contribute to the relaunch of the Whitchurch Folk Festival, head to the Paul Sartin Much Loved page. For more info on the Whitchurch Folk Club’s tribute to Paul Sartin, follow this link.